|

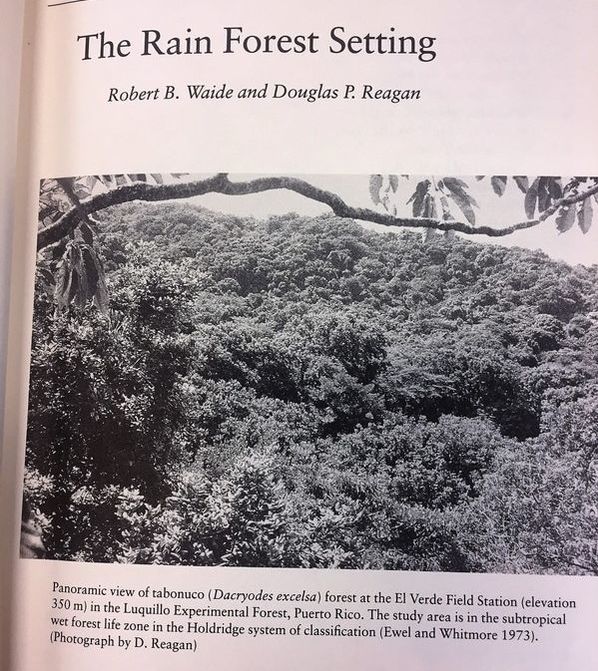

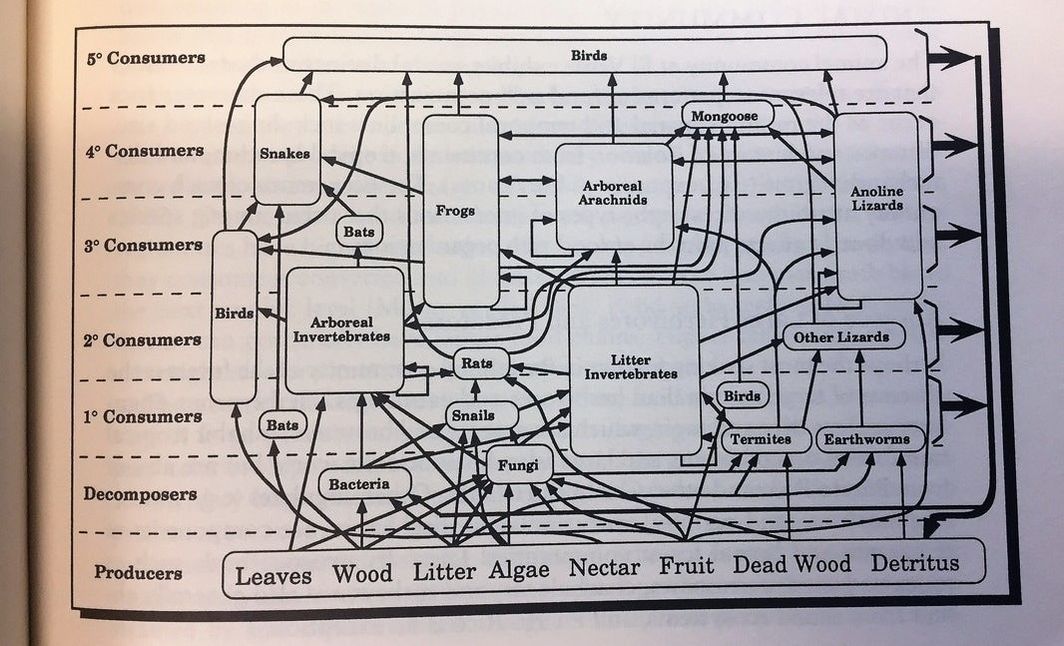

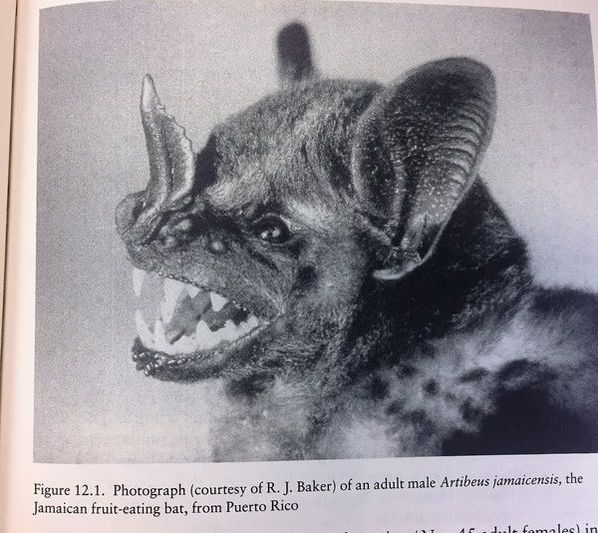

My favorite ecosystem is the subtropical montane Tabonuco forest of the Luquillo Mountains in northeastern Puerto Rico. The system is described as “aseasonal” and everwet, receiving >3500 mm/year rainfall with temperatures ranging between 20 and 23°C. The complete food web is documented in Reagan and Waide (1996). When published this book revolutionized the understanding of food webs, as it was the first book to fully document a food web of tropical rain forest. Forest species richness is greater than temperate forests, but less than tropical forests at similar latitudes due to an island effect, and measures around 200 species. Bird and ant richness is on par with other tropical forests, but there are fewer beetles than continental tropical forests. Faunal richness is low, lacking large-bodied herbivores, however frogs and lizards are present at very high densities. In fact, the ecosystem has the highest densities of Etherodactylus coqui frogs anywhere in the world (3200 adults and 17000 juveniles/ha). First and second-order headwater streams dissect the forest and harbor high densities of freshwater shrimp, land-dwelling crabs and small-bodied fish (e.g., gobies). Given the community and abundances of organisms, traditional food web theory would predict that the food web of such an ecosystem should be relatively simple, with 3 to 4 trophic levels. However, researchers found that on average the food web was more complex, with on average 8.5 links per food chain, with several reciprocal loops. They also found the number of links in the food web was variable across different habitats in the ecosystem, and that within habitats the food web is partitioned into diurnal and nocturnal components with different predator and prey interactions. Notably, without large herbivores, food chains were longer (not shorter) due to the higher trophic efficiency of cold-blooded organisms (i.e., frogs, lizards) relative to larger warmer-bodied organisms with higher metabolic rates. Most of the organisms are omnivorous making species interactions strong, but complex and variable. From a food webs perspective, ecosystems are stable if trophic interactions compensate environmental fluctuations and return to previous form following disturbance. Conveniently Hurricane Hugo severely damaged the forest in September 1988, providing an opportunity to evaluate the stability of the food web. Forest structure following Hurricane Hugo ‘resembled a forest of telephone poles among 3 to 5-m-deep piles of leaf and branch debris’ (pgs. 331-332). Despite serious short-term effects on the biota, the ecosystem is stable, as the food web has been completely recovered and can be viewed in its full glory, at present day, with a quick visit to El Verde Field Station in Puerto Rico. For example, not only has forest structure recovered, but so have Antillean fruit bat abundances after severe reductions in juvenile survival and female fecundity rates immediately following Hurricane Hugo. The ability for this ecosystem to recover the form, complexity, and connections of the food web following catastrophic hurricane disturbances points to a high degree of ecosystem stability and resilience.♠

1 Comment

|

AuthorJames "Aaron" Hogan is an ecologist interested in plant biodiversity, forests and global change. Archives

November 2021

Categories |